Wednesday, December 30, 2015

ch16

16 16a 16b 16c 16d 16e 16f 16g

Ch16

TS32-47

?MS538-566

finished before 07Feb 1905 [L2-81]

solitariness, verse-obsession

"Isolation is the first principle of artistic economy."

searching for evolutionary theory of verse

SD contemptuous of students' laughing at his condemnation of Othello

students reject art, SD redoubles resistance to this 'conspiracy'

let them meet him on his ground

Europe was initiating revolutions

throwing caution to the wind, reputation for wildness, chastity abandoned

walks with Maurice, diary, shows poems

decadence "a process to life through corruption"

poem

cutting classes, walking, skirtchasing

spurns fraud of college life

howling dog epiphany

SD popular as personality, excused for artistic temperament

McCann, orator, Cranly, Madden

SD's manner excuses his mad tastes

talk scheduled

reporter baffled by Maeterlinck

Ibsen influence reconciles intelligence with 'monster'

like Rousseau above contradictions

SD spokesman for notoriety of Ibsen

Daniels' Sunday evenings, music and games and recitations

Ibsen who's who, stupidity of pretty daughter

Emma

announces 'Drama and Life' (actually Oct 1899)

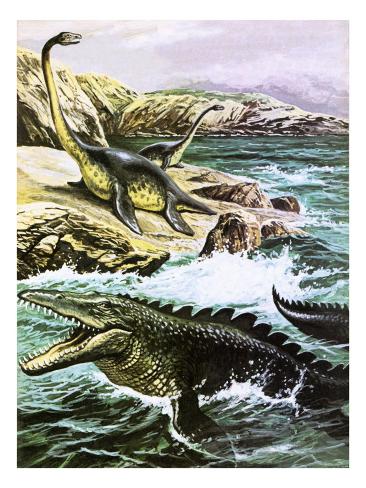

Plesiosaurus

Lessing: [EB] Laocoon [German]

antiphon

07Feb 1905 "I am 'working in' Hairy Jaysus at present. Do you not think the search for heroics damn vulgar-- and yet how are we to describe Ibsen?" [L2-80]

Maeterlinck: Joyce's oldest known copies of M's works are dated 1899, but the conversation with the journalist was probably after the 1900 Ibsen review.

Rousseau stole a ribbon, not spoons

Berlin: Ibsen's "John Gabriel Borkmann" was probably produced in 1897

Cavalier beard: [pic]

16 16a 16b 16c 16d 16e 16f 16g

Sunday, December 27, 2015

ch16a

16 16a 16b 16c 16d 16e 16f 16g

Their Eminences of the Holy College are hardly more scrupulous solitaries during the ballot for Christ's vicar than was Stephen at this time. He wrote a great deal of verse and, in default of any better contrivance, his verse allowed him to combine the offices of penitent and confessor. He sought in his verses to fix the most elusive of his moods and he put his lines together not word by word but letter by letter. He read Blake and Rimbaud on the values of letters and even permuted and combined the five vowels to construct cries for primitive emotions. To none of his former fervours had he given himself with such a whole heart as to this fervour; a the monk now seemed to him no more than half the artist. He persuaded himself that it is necessary for an artist to labour incessantly at his art if he wishes to express completely even the simplest conception and he believed that every moment of inspiration must be paid for in advance. He was not convinced of the truth of the saying "The poet is born, not made" but he was quite sure of the truth of this at least: "The poem is made not born." The burgher notion of the poet Byron in undress pouring out verses just as a city fountain pours out water seemed to him characteristic of most popular judgments on esthetic matters and he combated the notion at its root a by saying solemnly to Maurice — Isolation is the first principle of artistic economy.

PoA04: "Isolation, he had once written, is the first principle of artistic economy"

Stephen did not attach himself to art in any spirit of youthful dillettantism but strove to pierce to the significant heart of everything. a He doubled backwards into the past of humanity and caught glimpses of emergent art as one might have a vision of the pleisiosauros emerging from his ocean of slime. He seemed almost to hear the simple cries of fear and joy and wonder which are antecedent to all song, the savage rhythms of men pulling at the oar, to see the rude scrawls and the portable gods of men whose legacy Leonardo and Michelangelo inherit. And over all this chaos of history and legend, of fact and supposition, he strove to draw out a line of order, to reduce the abysses of the past to order by a diagram. The treatises which were recommended to him he found valueless and trifling; the Laocoon of Lessing irritated him. He wondered how the world could accept as valuable contributions such fanciful generalisations. What finer certitude could be attained by the artist if he believed that ancient art was plastic and that modern art was pictorial — ancient art in this context meaning art between the Balkans and the Morea and modern art meaning art anywhere between the Caucasus and the Atlantic except in the sacrosanct region. A great contempt devoured him for the critics who considered "Greek" and "classical" interchangeable terms and so full was he of intemperate anger that when Father Butt gave 'Othello' as the subject for the essay of the week Stephen lodged on the following Monday a profuse, downright protest against the 'masterpiece.' The young men in the class laughed and Stephen, as he looked contemptuously at the laughing faces, thought of a self-submersive reptile.

Balkans/Morea map

No-one would listen to his theories: no-one was interested in art. The young men in the college regarded art as a continental vice and they said in effect, "If we must have art are there not enough subjects in Holy Writ?" — for an artist with them was a man who painted pictures. It was a bad sign for a young man to show interest in anything but his examinations or his prospective 'job.' It was all very well to be able to talk about it but really art was all 'rot': besides it was probably immoral; they knew (or, at least, they had heard) about studios. They didn't want that kind of thing in their country. Talk about beauty, talk about rhythms, talk about esthetic — they knew what all the fine talk covered. One day a big countrified student came over to Stephen and asked:

— Tell us, aren't you an artist?

Stephen gazed at the idea-proof young man, without answering.

— Because if you are why don't you wear your hair long?

A few bystanders laughed at this and Stephen wondered for which of the learned professions the young man's father designed him.

conventionally just law, medicine, or theology

16 16a 16b 16c 16d 16e 16f 16g

Thursday, December 24, 2015

ch16b

16 16a 16b 16c 16d 16e 16f 16g

In spite of his surroundings Stephen continued his labours of research and all the more ardently since he imagined they had been put under ban. It was part of that ineradicable egoism which he was afterwards to call redeemer that he conceived converging to him the deeds and thoughts of his microcosm. Is the mind of youth medieval that it is so divining of intrigue? Field-sports (or their equivalent in the world of mentality) are perhaps the most effective cure and Anglo-Saxon educators favour rather a system of hardy brutality. But for this fantastic idealist, eluding the grunting booted apparition with a bound, the mimic warfare was no less ludicrous than unequal in a ground chosen to his disadvantage. Behind the rapidly indurating shield the sensitive answered: Let the pack of enmities come tumbling and sniffing to my highlands after their game. There was his ground and he flung them disdain from flashing antlers.

from 1904 PoA: "It was part of that ineradicable egoism which he was afterwards to call redeemer that he imagined converging to him the deeds and thoughts of the microcosm. Is the mind of boyhood medieval that it is so divining of intrigue? Field sports (or their correspondent in the world of mentality) are perhaps the most effective cure, but for the fantastic idealist, eluding the grunting booted apparition with a bound, the mimic hunt was no less ludicrous than unequal in a ground chosen to his disadvantage. But behind the rapidly indurating shield the sensitive answered. Let the pack of enmities come tumbling and sniffing to the highlands after their game— there was his ground: and he flung them disdain from flashing antlers."

Indeed he felt the morning in his blood: he was aware of some movement already proceeding a out in Europe. Of this last phrase he was fond for it seemed to him to unroll the measurable world before the feet of the islanders. Nothing could persuade him that the world was such as Father Butt's students conceived it. He had no need for the cautions which were named indispensable, no reverence for the proprieties which were called the bases of life. He was an enigmatic figure in the midst of his shivering society where he enjoyed a reputation. His comrades hardly knew how far to venture with him and professors pretended to think his seriousness a sufficient warrant against any practical disobedience.-On his side chastity, having been found a great inconvenience, had been quietly abandoned and the youth amused himself in the company of certain of his fellow-students among whom (as the fame went) wild living was not unknown. The Rector of Belvedere had a brother who was at this time a student in the college and one night in the gallery of the Gaiety (for Stephen had become a constant 'god') another Belvedere boy, a who was also a student in the college, bore scandalous witness into Stephen's ear.

— I say, Daedalus.

— Well?

— I wonder what MacNally would say if he met his brother — you know the fellow in the college?

— Yes.

— I saw him in Stephen's Green the other day with a tart. I was just thinking if MacNally saw him...

The informant paused: and then, afraid of over-implication and with an air of a connoisseur, he added seriously:

— Of course she was... all right.

16 16a 16b 16c 16d 16e 16f 16g

Monday, December 21, 2015

ch16c

16 16a 16b 16c 16d 16e 16f 16g

Every evening after tea Stephen left his house and set out for the city, Maurice at his side. The elder smoked cigarettes and the younger ate lemon drops and, aided by these animal comforts, they beguiled the long journey with philosophic discourse. Maurice was a very attentive person and one evening he told Stephen that he was keeping a diary of their conversations. Stephen asked to see the diary but Maurice said it would be time enough for that at the end of the first year. Neither of the youths had the least suspicion of themselves; they both looked upon life with frank curious eyes (Maurice naturally serving himself with Stephen's vision when his own was deficient) and they both felt that it was possible to arrive at a sane understanding of so-called mysteries if one only had patience enough. On their way in every evening the heights of argument were traversed and the younger boy aided the elder bravely in the building of an entire science of esthetic. They spoke to each other very decisively and Stephen found Maurice very useful for raising objections. When they came to the gate of the Library they used to stand to finish some branch of their subject and often the discussion was so protracted that Stephen would decide that it was too late to go in to read and so they would set their faces for Clontarf and return in the same manner. Stephen, after certain hesitations, showed Maurice the first-fruits of his verse and Maurice asked who the woman was. Stephen looked a little vaguely before him before answering and in the end had to answer that he didn't know who she was.

map

To this unknown verses were now regularly inscribed and it seemed that the evil dream of love which Stephen chose to commemorate in these verses lay veritably upon the world now in a season of a damp violet mist. He had abandoned his Madonna, he had forsaken his word and he had withdrawn sternly from his little world and surely it was not wonderful that his solitude should propel him to frenetic outbursts of a young man's passion and to outbursts of loneliness? This quality of the mind which so reveals itself is called (when incorrigible) a decadence but if we are to take a general view of the world we cannot but see a process to life through corruption. There were moments for him, however, when such a process would have seemed intolerable, life on any common terms an intolerable offence, and at such moments he prayed for nothing and lamented for nothing but he felt with a sweet sinking of consciousness that if the end came to him it was in the arms of the unknown that it would come to him:

The dawn awakes with tremulous alarms,

How grey, how cold, how bare!

O, hold me still white arms, encircling arms

And hide me, heavy hair!

Life is a dream, a dream. The hour is done

And antiphon is said.

We go from the light and falsehood of the sun

To bleak wastes of the dead.

16 16a 16b 16c 16d 16e 16f 16g

Friday, December 18, 2015

ch16d

16 16a 16b 16c 16d 16e 16f 16g

Little by little Stephen became more irregular in his attendances at the college. He would leave his house every morning at the usual hour and come into the city on the tram. But always at Amiens St Station he would get down and walk and as often as not he would decide to follow some trivial indication of city life instead of entering the oppressive life of the College. He often walked thus for seven or eight hours at a stretch without feeling in the least fatigued. The damp Dublin winter seemed to harmonise with his inward sense of unreadiness and he did not follow the least of feminine provocations through tortuous, unexpected ways any more zealously than he followed through ways even less satisfying the nimble movements of the elusive one. What was that One: arms of love that had not love's malignity, laughter running upon the mountains of the morning, an hour wherein might be encountered the incommunicable? And if the heart but trembled an instant at some approach to that he would cry, youthfully, passionately "It is so! It is so! Life is such as I conceive it." He spurned from before him the stale maxims of the Jesuits and he swore an oath that they should never establish over him an ascendancy. He spurned from before him a world of the higher culture in which there was neither scholarship nor art nor dignity of manners — a world of trivial intrigues and trivial triumphs. Above all he spurned from before him the company of decrepit youth — and he swore an oath that never would they establish with him a compact of fraud. Fine words! fine oaths! crying bravely and passionately even in the teeth of circumstances. For not unfrequently in the pauses of rapture Dublin would lay a sudden hand upon his shoulder, and the chill of the summons would strike to his heart. One day he passed on his homeward journey through Fairview. At the fork of the roads before the swampy beach a big dog was recumbent. From time to time he lifted his muzzle in the vapourous air, uttering a prolonged sorrowful howl. People had gathered on the footpaths to hear him. Stephen made one of them till he felt the first drops of rain, and then he continued his way in silence under the dull surveillance of heaven, hearing from time to time behind him the strange lamentation.

from an epiphany: "Dull clouds have covered the sky. Where three roads meet and before a swampy beach a big dog is recumbent. From time to time he lifts his muzzle in the air and utters a prolonged sorrowful howl. People stop to look at him and pass on; some remain, arrested, it may be, by that lamentation in which they seem to hear the utterance of their own sorrow that had once its voice but now is voiceless, a servant of laborious days. Rain begins to fall."

It was natural that the more the youth sought solitude for himself the more his society sought to prevent his purpose. Though he was still in his first year he was considered a personality and there were even many who thought that though his theories were a trifle ardent they were not without meaning. Stephen came seldom to lectures, prepared nothing and absented himself from term examinations and not merely was no remark passed on these extravagances but it was supposed probable that he represented really the artistic type and that he was, after the fashion of that little known tribe, educating himself. It must not be supposed that the popular University of Ireland lacked an intelligent centre. Outside the compact body of national revivalists there were here and there students who had certain ideas of their own and were more or less tolerated by their fellows. For instance there was a serious young feminist named McCann — a blunt brisk figure, wearing a Cavalier beard and shooting-suit, and a steadfast reader of the Review of Reviews. The students of the college did not understand what manner of ideas he favoured and they considered that they rewarded his originality sufficiently by calling him 'Knickerbockers.' There was also the College orator — a most amenable young man who spoke at all meetings. Cranly too was a personality and Madden had soon been recognised as the a spokesman of the patriotic party. Stephen may be said to have occupied the position of notable-extraordinary: very few had ever heard of the writers he was reported to read and those who had knew them to be mad fellows. At the same time as Stephen's manner was so unbending to all it was supposed that he had preserved his sanity entire and safely braved temptations. People began to defer to him, to invite him to their houses and to present serious faces to him. His were simply theories and, as he had as yet committed no breach of the law, he was respectfully invited to read a paper before the Literary and Historical Society of the College. The date was fixed for the end of March and the title of the paper was announced as 'Drama and Life.' Many risked the peril of rebuff to engage the young eccentric in talk but Stephen preserved a disdainful silence. One night as he was returning from a party a reporter of one of the Dublin papers, who had been introduced that evening to the prodigy, approached him and after a few exchanges said to him tentatively:

|

| Skeffington still wearing knickerbockers in 1916 |

— I was reading of that writer... what's this you call him... Maeterlinck the other day... you know?

— Yes.

— I was reading, The Intruder I think was the name of it... Very... curious play...

Stephen had no wish to talk to the man about Maeterlinck and on the other hand he did not like to offend by the silence which the remark and the tone and the intention all seemed to deserve so he cast about quickly in his mind for some non-committal banality with which to pay the debt. At last he said:

— It would be hard to put it on the stage.

The journalist was quite satisfied at this exchange as if it was just this impression and no other which Maeterlinck's play had produced upon him. He assented with conviction:

— O yes!... next to impossible...

16 16a 16b 16c 16d 16e 16f 16g

Tuesday, December 15, 2015

ch16e

16 16a 16b 16c 16d 16e 16f 16g

Allusions of such a kind to what he held so dear at heart wounded Stephen deeply. It must be said simply and at once that at this time Stephen suffered the most enduring influence of his life.

23yo writing about 17yo

The spectacle of the world which his intelligence presented to him with every sordid and deceptive detail set side by side with the spectacle of the world which the monster in him, now grown to a reasonably heroic stage, presented also had often filled him with such sudden despair as could be assuaged only by melancholy versing. He had all but decided to consider the two worlds as aliens one to another — however disguised or expressed the most utter of pessimisms — when he encountered through the medium of hardly procured translations the spirit of Henrik Ibsen. He understood that spirit instantaneously. Some years before this same instantaneous understanding had occurred when he had read the very puzzled, apologetic account which Rousseau's English biographer had given of the young philosopher's stealing his mistress's spoons and allowing a servant-girl to be accused of the theft at the very moment when he was beginning his struggle for Truth and Liberty.

why not Rousseau's own Confessions? [ebook?]

(it was a ribbon, not spoons)

Just as then with the perverse philosopher so now: Ibsen had no need of apologist or critic: the minds of the old Norse poet and of the perturbed young Celt met in a moment of radiant simultaneity. Stephen was captivated first by the evident excellence of the art: he was not long before he began to affirm, out of a sufficiently scanty knowledge of the tract, of course, that Ibsen was the first among the dramatists of the world. In translations of the Hindu or Greek or Chinese theatres he found only anticipations of or attempts and in the French classical, and the English romantic, theatres anticipations less distinct and attempts less successful. But it was not only this excellence which captivated him: it was not that which he greeted gladly with an entire joyful spiritual salutation. It was the very spirit of Ibsen himself that was discerned moving behind the impersonal manner of the artist: a mind of sincere and boylike bravery, of disillusioned pride, of minute and wilful energy. Let the world solve itself in whatsoever fashion it pleased, let its putative Maker justify Himself by whatsoever processes seemed good to Him, one could scarcely advance the dignity of the human attitude a step beyond this answer. Here and not in Shakespeare or Goethe was the successor to the first poet of the Europeans, here, as only to such purpose in Dante, a human personality had been found united with an artistic manner which was itself almost a natural phenomenon: and the spirit of the time united one more readily with the Norwegian than with the Florentine.

The young men of the college had not the least idea who Ibsen was but from what they could gather here and there they surmised that he must be one of the atheistic writers whom the papal secretary puts on the Index. It was a novelty to hear anyone mention such a name in their college but as the professors gave no lead in condemnation they concluded that they had better wait. Meanwhile they were somewhat impressed: many now began to say that though Ibsen was immoral he was a great writer and one of the professors was heard to say that when he was in Berlin last summer on his holidays there had been a great deal of talk about some play of Ibsen's which was being performed at one of the theatres. Stephen had begun to study Danish instead of preparing his course for the examination and this fact was magnified into a report that he was a profit by rumours which he took no trouble to contradict. He smiled to think that these people in their hearts feared him as an infidel and he marvelled at the quality of their supposed beliefs. Father Butt talked to him a great deal and Stephen was nothing loth to make himself the herald of a new order. He never spoke with heat and he argued always as if he did not greatly care which way the argument went, at the same time never losing a point. The Jesuits and their flocks may have said to themselves: the a youthful seeming-independent we know, and the appeasable patriot we know, but what are you? They played up to him very well, considering their disadvantages, and Stephen could not understand why they took the trouble to humour him.

— Yes, yes, said Father Butt one day after one of these scenes, I see... I quite see your point... It would apply of course to the dramas of Turgenieff?

Stephen had read and admired certain translations of Turgenieff's novels and stories and he asked therefore with a genuine note in his voice:

— Do you mean his novels?

— Novels, yes, said Father Butt swiftly,... his novels, to be sure... but of course they are dramas... are they not, Mr Daedalus?

16 16a 16b 16c 16d 16e 16f 16g

Saturday, December 12, 2015

ch16f

16 16a 16b 16c 16d 16e 16f 16g

Very often Stephen used to visit at a house in Donnybrook the atmosphere of which was compact of liberal patriotism and orthodox study. There were several marriageable daughters in the family and whenever any promise on the part of a young student was signalled he was sure to receive an invitation to this house. The young feminist McCann was a constant visitor there and Madden used to visit occasionally. The father of the family was an elderly man who played chess on week evenings with his grown-up sons and assisted on Sunday evenings at a round of games and music. The music was supplied by Stephen. There was an old piano in the room and when the room was tired of games one of the daughters used to come over smilingly to Stephen and a ask him to sing them some of his beautiful songs. The keys of the piano were worn away and sometimes the notes would not sound but the tone was soft and mellow and Stephen used to sit down and sing his beautiful songs to the polite, tired, unmusical audience. The songs, for him at least, were really beautiful — the old country songs of England and the elegant songs of the Elizabethans. The 'moral' of these songs was sometimes a little dubious and Stephen's ear used to catch at once the note of qualification in the applause that followed them. The studious daughters found these songs very quaint but Mr Daniel said that Stephen should sing operatic music if he wanted to have his voice heard properly. In spite of the entire absence of sympathy between this circle and himself Stephen was very much at ease in it and he was, as they bade him be, very much 'at home' as he sat on the sofa counting the lumps of horsehair with the ends of his a fingers, and listening to the conversation. The young men and the daughters amused themselves tolerably under Mr Daniel's eye but whenever there was an approach to artistic matters during the process of their games Stephen with egoistic humour imagined his presence acting as a propriety. He could see seriousness developing on the shrewd features of a young man who had to put a certain question to one of the daughters:

Sheehys in 1901

— I suppose it's my turn now... Well... let me see... (and here he became as serious as a young man, who has been laughing very much for a full five minutes, can become)... Who is your favourite poet, Annie?

Annie thought for a few moments: there was a pause. Annie and the young man were 'doing' the same course.

—... German?

—... Yes.

Annie thought for another few moments while the table waited to be edified.

— I think... Goethe.

McCann used very often to organise a charades in which he used to take the most violent parts. The charades were very farcical and everyone took his part with goodwill, Stephen as well as the others. Stephen would play his quiet deliberative manner off against McCann's uproarious acting and for this reason the two were often 'picked' together. These charades wearied Stephen a little but McCann was very much given to organising them as he was of the opinion that amusement is necessary for the bodily welfare of mankind. The young feminist's Northern accent always excited laughter and his face, adorned with its Cavalier beard, was certainly capable of brazen grimaces. In the college McCann had never been assimilated on account of his 'ideas' but here he partook of the inner life of the family. In this house it was the custom to call a young visitor by his Christian name a little too soon and though Stephen was spared the compliment, McCann was never spoken of as anything but 'Phil.' Stephen used to call him 'Bonny Dundee' nonsensically associating his brisk name and his brisk manners with the sound of the line:

Come fill up my cup, come fill up my can.

Whenever the evening assumed the character of a serious affair Mr Daniel would be asked to recite something for the company. Mr Daniel had formerly been the manager of a theatre in Wexford and he had often spoken at public meetings through the country. He recited national pieces in a stern declamatory fashion amid attentive silence. The daughters also recited. During these recitations Stephen's eye never moved from the picture of the Sacred Heart which hung right above the head of the reciter's head. The Miss Daniels were not so imposing as their father and their dress was {illegible word} somewhat colleen. Jesus, moreover, exposed his heart somewhat too obviously in the cheap print: and Stephen's thoughts were usually fascinated to a pleasant stupor by these twin futilities. A parliamentary charade was frequent. Mr Daniel had sat for his county some years before and for this reason he was chosen to impersonate the Speaker of the House. McCann always represented a member of the Opposition and he spoke point-blank. Then a member would protest and there would be a make-believe of parliamentary manners.

cf ch17 below: "As in the Daniels' household he had seen people playing at being important..."

— Mr Speaker, I must ask...

— Order! Order!

— You know it's a lie!

— You must withdraw, Sir.

— As I was saying before the honourable gentleman interrupted we must...

— I won't withdraw.

— I must ask honourable members to preserve order in the House.

— I won't withdraw.

— Order! Order!

16 16a 16b 16c 16d 16e 16f 16g

Wednesday, December 9, 2015

ch16g

16 16a 16b 16c 16d 16e 16f 16g

Another favourite was "Who's Who." A person goes out of the room and the rest of the company choose the name of someone who is supposed to have special attractions for the absent player. This latter, when he returns to the company, has to ask questions all round and try to guess the name. This game was generally used to the discomfiture of the young male guests for the manner in which it was played suggested that each young student had an affair of the heart with some young lady within tolerable distance of him: but the young men, who were at first surprised by these implications, ended by looking as if they thought that the sagacity of the other players had just forestalled them in an unexpected, not unpleasant, discovery. No such suggestion could be seriously made by the company to fit Stephen's case and so the first time he played the game they chose differently for him. The players were unable to answer his questions when he returned to the room: such questions as: "Where does the person live?" "Is the person married or single?" "What age is the person?" could not be answered by the circle until McCann had been consulted in a swift undertone. The answer "Norway" gave Stephen the clue at once and so the game ended and the company proceeded to divert themselves as before this serious interruption. Stephen sat down beside one of the daughters and, while admiring the rural comeliness of her features, waited quietly for her first word which, he knew, would destroy his satisfaction. Her large handsome eyes looked at him for a while as if they were a about to trust him and then she said:

— How did you guess it so quickly?

— I knew you meant him. But you're wrong about his age.

Others had heard this: but she was impressed by a possible vastness of the unknown, complimented to confer with one who conferred directly with the exceptional. She leaned forward to speak with soft seriousness.

— Why, how old is he?

— Over seventy.

— Is he?

from an epiphany:

"Dublin: at Sheehy's, Belvedere Place

Joyce— I knew you meant him. But you're wrong about his age.

Maggie Sheehy— (leans forward to speak seriously) Why, how old is he?

Joyce— Seventy-two.

Maggie Sheehy— Is he?"

Stephen now imagined that he had explored this region sufficiently and he would have discontinued his visits had not two causes induced him to continue. The first cause was the unpleasant character of his home and the second was the curiosity occasioned by the advent of a new figure. One evening while he was musing on the horsehair sofa he heard his name called and stood up to be introduced. A dark a full-figured girl was standing before him and, without waiting for Miss Daniel's introduction, she said:

— I think we know each other already.

She sat beside him on the sofa and he found out that she was studying in the same college with the Miss Daniels and that she always signed her name in Irish. She said Stephen should a learn Irish too and join the League. A young man of the company, whose face wore always the same look of studied purpose, spoke with her across Stephen addressing her familiarly by her Irish name. Stephen therefore spoke very formally and always addressed her as 'Miss Clery.' She seemed on her part to include him in the a general scheme of her nationalising charm: and when he helped her into her jacket she allowed his hands to rest for a moment against the warm flesh of her shoulders.

16 16a 16b 16c 16d 16e 16f 16g

Sunday, November 29, 2015

ch17

Ch17

TS48-68

?MS567-604

written Feb 1905 [L2-81] (JAJ started wearing glasses again at this point, after ten years of nearsightedness)

Maurice forbidden walks, SD threatened with withdrawal of support

SD determined to live, rejoices in self-centeredness

finds solitude restful, making friends at school

writing paper to try and win converts

SD debates McCann's theories-- Socratic dialog

SD trembles to think of McCann's "unhorizoned doggedness working its way backwards" [ = frigging??? unhorizoned = shortsighted? backwards to virginity? to the womb?! sex is the spirit working backwards to womb??]

license as a sin against the future

Ibsen not a moralist

SD feigns interest in Irish to get close to Emma, via Madden

SD hates church more than English, Madden panders to church for support

SD sees no gain in Irish language

others adjust to idea of SD studying Irish

Maurice's retreat, SD marvels how far he's come, Maurice's seriousness

no 'companions'-- fear of SD?

Maurice's prosaic self-contemplation appalls SD

Wed night Irish class, Mr Hughes

the word for 'love' discomfits a young man

Citizen, Madden, Griffith in Cooney's

nationalism as bogus fraud

Bacon quote: [etext]

Silas Verney: historical novel of 17th C by Edgar Pickering

JAJ and JFB attend Gaelic meeting May 1900 [historical context]

Stannie's retreat Dec 1898

28Feb to Stannie: "It seems to me that what astonishes most people in the length of the novel is the extraordinary energy in the writer and his extraordinary patience. It would be easy for me to do short novels if I chose but what I want to wear away in this novel cannot be worn away except by constant dropping. Gogarty used to pipe '63' in treble when I told him the number of the chapters. I am not quite satisfied with the title 'Stephen Hero' and am thinking of restoring the original title of the article 'A Portrait of the Artist' or perhaps better 'Chapters in the Life of a Young Man'." [SL56]

Friday, November 27, 2015

ch17a

17 17a 17b 17c 17d 17e 17f 17g 17h

Stephen's home-life had by this time grown sufficiently unpleasant: the direction of his development was against the stream of tendency of his family. The evening walks with Maurice had been prohibited for it had become evident that Stephen was corrupting his brother to idle habits. Stephen was harassed very much by enquiries as to his progress at the College and Mr Daedalus, meditating upon the evasive answers, had begun to express a fear that his son was falling into bad company. The youth was given to understand that if he did not succeed brilliantly at the coming examination his career at the University would come to a close. He was not greatly troubled by this warning for he knew that his fate was, in this respect, with his godfather and not with his father. He felt that the moments of his youth were too precious to be wasted in a dull mechanical endeavour and he determined, whatever came of it, to prosecute his intentions to the end. His family expected that he would at once follow the path of remunerative respectability and save the situation but he could not satisfy his family. He thanked their intention: it had first fulfilled him with egoism; and he rejoiced that his life had been so self-centred. He felt however that there were activities which it a would be a peril to postpone.

Maurice accepted this prohibition with a bad grace and had to be restrained by his brother from overt disobedience. Stephen himself bore it lightly because he could ease himself greatly in solitude and for human channels, at the worst, he could resort to a few of his college-companions. He was now busily preparing his paper for the Literary and Historical Society and he took every precaution to ensure in it a maximum of explosive force. It seemed to him that the students might need only the word to enkindle them towards liberty or that, at least, his trumpet-call might bring to his side a certain minority of the elect. McCann was the Auditor of the Society and as he was anxious to know the trend of Stephen's paper the two used often to leave the Library at ten o'clock and walk towards the Auditor's lodgings, discussing. McCann enjoyed the reputation of a fearless, free-spoken young man but Stephen found it difficult to bring him to any fixed terms on matters which were held to be dangerous ground. McCann would talk freely on feminism and on rational life: he believed that the sexes should be educated together in order to accustom them early to each other's influences and he believed that women should be afforded the same opportunities as were afforded to the so-called superior sex and he believed that women had the right to compete with men in every branch of social and intellectual activity. He also held the opinion that a man should live without using any kind of stimulant, that he had a moral obligation to transmit to posterity sound minds in sound bodies, and that he should not allow himself to be dictated to on the subject of dress by any conventions. Stephen delighted to riddle these theories with agile bullets.

Ellmann says the Auditor was Arthur Clery (31yo barrister in 1911)

|

| 21yo in 1901 |

Skeffington [1909 map] [1901 census] ('Roman Catholic Professor of Languages')

— You would have no sphere of life closed to them?

— Certainly not.

— Would you have the soldiery, the police and the fire-brigade recruited also from them?

— There are certain social duties for which women are physically unfitted.

— I believe you.

— At the same time they should be allowed to follow any civil profession for which they have an aptitude.

— Doctors and lawyers?

— Certainly.

— And what about the third learned profession?

— How do you mean?

— Do you think they would make good confessors?

— You are flippant. The Church does not allow women to enter the priesthood.

— O, the Church!

17 17a 17b 17c 17d 17e 17f 17g 17h

Wednesday, November 25, 2015

ch17b

17 17a 17b 17c 17d 17e 17f 17g 17h

Whenever the conversation reached this point McCann refused to follow it further. The discussions usually ended in a deadlock:

— But you go mountain-climbing in search of fresh air?

— Yes.

— And bathing in the summertime?

— Yes.

— And surely the mountain air and the salt water act as stimulants!

— Natural stimulants, yes.

— What do you call an unnatural stimulant?

— Intoxicating drinks.

— But they are produced from natural vegetable substances, aren't they?

— Perhaps, but by an unnatural process.

— Then you regard a brewer as a high thaumaturgist?

— Intoxicating drinks are manufactured to satisfy artificially induced appetites. Man, in the normal condition, has no need for such props to life.

— Give me an example of man in what you call 'the normal condition.'

— A man who lives a healthy, natural life.

— Yourself?

— Yes.

— Do you then represent normal humanity?

— I do.

— Then is normal humanity short-sighted and tone-deaf?

— Tone-deaf?

— Yes: I think you are tone-deaf.

— I like to hear music.

— What music?

— All music.

— But you cannot distinguish one air from another.

— No: I can recognise some airs.

— For instance?

— I can recognise 'God save the Queen.'

— Perhaps because all the people stand up and take off their hats.

— Well, admit that my ear is a little defective.

— And your eyes?

— They too.

— Then how do you represent normal humanity?

— In my manner of life.

17 17a 17b 17c 17d 17e 17f 17g 17h

Monday, November 23, 2015

ch17c

17 17a 17b 17c 17d 17e 17f 17g 17h

— Your wants and the manner in which you satisfy them,

— Exactly.

— And what are your wants?

— Air and food.

— Have you any subsidiary ones?

— The acquisition of knowledge.

— And you need also religious comforts?

— Maybe so... at times.

— And women... at times?

— Never!

This last word was uttered with a moral snap of the jaws and in such a business-like tone of voice that Stephen burst out into a fit of loud laughter. As for the fact, though he was very suspicious in this matter, Stephen was inclined to believe in McCann's chastity and much as he disliked it he chose to contemplate it rather than the contrary phenomenon. He almost trembled to think of that unhorizoned doggedness working its way backwards.

McCann's insistence on a righteous life and his condemnation of licence as a sin against the future both annoyed and stung Stephen. It annoyed him because it savoured so strongly of paterfamilias and it stung him because it seemed to judge him incapable of that part. In McCann's mouth he considered it unjust and unnatural and he fell back on a sentence of Bacon's. The care of posterity, he quoted, is greatest in them that have no posterity: and for the rest he said that he could not understand what right the future had to hinder him from any passionate exertions in the present.

— That is not the teaching of Ibsen, said McCann.

— Teaching! cried Stephen.

— The moral of Ghosts is just the opposite of what you say.

— Bah! You regard a play as a scientific document.

— Ghosts teaches self-repression.

— O Jesus! said Stephen in agony.

— This is my lodging, said McCann, halting at the gate. I must go in.

— You have connected Ibsen and Eno's fruit salt forever in my mind, said Stephen.

— Daedalus, said the Auditor crisply, you are a good fellow but you have yet to learn the dignity of altruism and the responsibility of the human individual.

17 17a 17b 17c 17d 17e 17f 17g 17h

Saturday, November 21, 2015

ch17d

17 17a 17b 17c 17d 17e 17f 17g 17h

Stephen had decided to address himself to Madden to ascertain where Miss Clery was to be found. He set about this task carefully. Madden and he were often together but their conversations were rarely serious and though the rustic mind of one was very forcibly impressed by the metropolitanism of the other both young men were on relations of affectionate familiarity. Madden who had previously tried in vain to infect Stephen with nationalistic fever was surprised to hear these overtures of his friend. He was delighted at the prospect of making such a convert and he began to appeal eloquently to the sense of justice. Stephen allowed his critical faculty a rest. The so-desired community for the realising of which Madden sought to engage his personal force seemed to him anything but ideal and the liberation which would have satisfied Madden would by no means have satisfied him. The Roman, not the Sassenach, was for him the tyrant of the islanders: and so deeply had the tyranny eaten into all souls that the intelligence, first overborne so arrogantly, was now eager to prove that arrogance its friend. The watchcry was Faith and Fatherland, a sacred word in that world of cleverly inflammable enthusiasms. With literal obedience and with annual doles the Irish bid eagerly for the honour which was studiously withheld from them to be given to nations which in the past, as in the present, had never bent the knee but in defiance. While the multitude of preachers assured them that high honours were on the way and encouraged them ever to hope. The last should be first, according to the Christian sentiment, and whosoever humbled himself, exalted and in reward for several centuries of obscure fidelity the Pope's Holiness had presented a tardy cardinal to an island which was for him, perhaps, only the afterthought of Europe.

Madden was prepared to admit the truth of much of this but he gave Stephen to understand that the new movement was politic. If the least infidelity were hoisted on the standard the people would not flock to it and for this reason the promoters desired as far as possible to work hand in hand with the priests. Stephen objected that this working hand in hand with the priests had over and over again ruined the chances of revolutions. Madden agreed: but now at least the priests were on the side of the people.

— Do you not see, said Stephen, that they encourage the study of Irish that their flocks may be more safely protected from the wolves of disbelief; they consider it is an opportunity to withdraw the people into a past of literal, implicit faith?

— But really our peasant has nothing to gain from English Literature.

— Rubbish!

— Modern at least. You yourself are always railing...

— English is the medium for the Continent.

— We want an Irish Ireland.

— It seems to me you do not care what banality a man expresses so long as he expresses it in Irish.

— I do not entirely agree with your modern notions. We want to have nothing of this English civilisation.

— But the civilisation of which you speak is not English — it is Aryan. The modern notions are not English; they point the way of Aryan civilisation.

— You want our peasants to ape the gross materialism of the Yorkshire peasant?

— One would imagine the country was inhabited by cherubim. Damme if I see much difference in peasants: they all seem to me as like one another as a peascod is like another peascod. The Yorkshireman is perhaps better fed.

— Of course you despise the peasant because you live in the city.

— I don't despise his office in the least.

— But you despise him — he's not clever enough for you.

— Now, you know, Madden that's nonsense. To begin with he's as cute as a fox — try to pass a false coin on him and you'll see. But his cleverness is all of a low order. I really don't think that the Irish peasant represents a very admirable type of culture.

— That's you all out! Of course you sneer at him because he's not up-to-date and lives a simple life.

— Yes, a life of dull routine — the calculation of coppers, the weekly debauch and the weekly piety — a life lived in cunning and fear between the shadows of the parish chapel and the asylum!

— The life of a great city like London seems to you better?

— The intelligence of an English city is not perhaps at a very high level but at least it is higher than the mental swamp of the Irish peasant.

— And what about the two as moral beings?

— Well?

— The Irish are noted for at least one virtue all the world over.

— Oho! I know what's coming now!

— But it's a fact — they are chaste.

— To be sure.

— You like to run down your own people at every hand's turn but you can't accuse them...

— Very good: you are partly right. I fully recognise that my countrymen have not yet advanced as far as the machinery of Parisian harlotry because...

— Because...?

— Well, because they can do it by hand, that's why!

— Good God, you don't mean to say you think...

— My good youth, I know what I am saying is true and so do you know it. Ask Father Pat and ask Dr Thisbody and ask Dr Thatbody. I was at school and you were at school — and that's enough about it.

— O, Daedalus!

This accusation laid a silence on the conversation. Then Madden spoke:

— Well, if these are your ideas I don't see what you want coming to me and talking about learning Irish.

— I would like to learn it — as a language, said Stephen lyingly. At least I would like to see first.

— So you admit you are an Irishman after all and not one of the red garrison.

— Of course I do.

— And don't you think that every Irishman worthy of the name should be able to speak his native tongue?

— I really don't know.

— And don't you think that we as a race have a right to be free?

— O, don't ask me such questions, Madden. You can use these phrases of the platform but I can't.

— But surely you have some political opinions, man!

— I am going to think them out. I am an artist, don't you see? Do you believe that I am?

— O, yes, I know you are.

— Very well then, how the devil can you expect me to settle everything all at once? Give me time.

So it was decided that Stephen was to begin a course of lessons in Irish. He bought the O'Growney's primers published by the Gaelic League but refused either to pay a subscription to the League or to wear the badge in his buttonhole. He had found out what he had desired, namely, the class in which Miss Clery was. People at home did not seem opposed to this new freak of his. Mr Casey taught him a few Southern songs in Irish and always raised his glass to Stephen saying "Sinn Fein" instead of "Good Health." Mrs Daedalus was probably pleased for she thought that the superintendence of priests and the society of harmless enthusiasts might succeed in influencing her son in the right direction: she had begun to fear for him. Maurice said nothing and asked no questions. He did not understand what made his brother associate with the patriots and he did not believe that the study of Irish seemed in any way useful to Stephen: but he was silent and waited. Mr Daedalus said that he did not mind his son's learning the language so long as it did not keep him from his legitimate work.

17 17a 17b 17c 17d 17e 17f 17g 17h

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)