Sunday, December 27, 2015

ch16a

16 16a 16b 16c 16d 16e 16f 16g

Their Eminences of the Holy College are hardly more scrupulous solitaries during the ballot for Christ's vicar than was Stephen at this time. He wrote a great deal of verse and, in default of any better contrivance, his verse allowed him to combine the offices of penitent and confessor. He sought in his verses to fix the most elusive of his moods and he put his lines together not word by word but letter by letter. He read Blake and Rimbaud on the values of letters and even permuted and combined the five vowels to construct cries for primitive emotions. To none of his former fervours had he given himself with such a whole heart as to this fervour; a the monk now seemed to him no more than half the artist. He persuaded himself that it is necessary for an artist to labour incessantly at his art if he wishes to express completely even the simplest conception and he believed that every moment of inspiration must be paid for in advance. He was not convinced of the truth of the saying "The poet is born, not made" but he was quite sure of the truth of this at least: "The poem is made not born." The burgher notion of the poet Byron in undress pouring out verses just as a city fountain pours out water seemed to him characteristic of most popular judgments on esthetic matters and he combated the notion at its root a by saying solemnly to Maurice — Isolation is the first principle of artistic economy.

PoA04: "Isolation, he had once written, is the first principle of artistic economy"

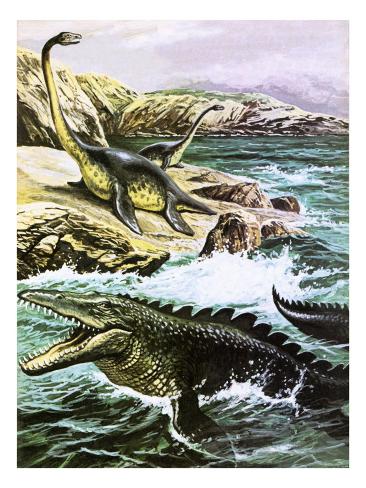

Stephen did not attach himself to art in any spirit of youthful dillettantism but strove to pierce to the significant heart of everything. a He doubled backwards into the past of humanity and caught glimpses of emergent art as one might have a vision of the pleisiosauros emerging from his ocean of slime. He seemed almost to hear the simple cries of fear and joy and wonder which are antecedent to all song, the savage rhythms of men pulling at the oar, to see the rude scrawls and the portable gods of men whose legacy Leonardo and Michelangelo inherit. And over all this chaos of history and legend, of fact and supposition, he strove to draw out a line of order, to reduce the abysses of the past to order by a diagram. The treatises which were recommended to him he found valueless and trifling; the Laocoon of Lessing irritated him. He wondered how the world could accept as valuable contributions such fanciful generalisations. What finer certitude could be attained by the artist if he believed that ancient art was plastic and that modern art was pictorial — ancient art in this context meaning art between the Balkans and the Morea and modern art meaning art anywhere between the Caucasus and the Atlantic except in the sacrosanct region. A great contempt devoured him for the critics who considered "Greek" and "classical" interchangeable terms and so full was he of intemperate anger that when Father Butt gave 'Othello' as the subject for the essay of the week Stephen lodged on the following Monday a profuse, downright protest against the 'masterpiece.' The young men in the class laughed and Stephen, as he looked contemptuously at the laughing faces, thought of a self-submersive reptile.

Balkans/Morea map

No-one would listen to his theories: no-one was interested in art. The young men in the college regarded art as a continental vice and they said in effect, "If we must have art are there not enough subjects in Holy Writ?" — for an artist with them was a man who painted pictures. It was a bad sign for a young man to show interest in anything but his examinations or his prospective 'job.' It was all very well to be able to talk about it but really art was all 'rot': besides it was probably immoral; they knew (or, at least, they had heard) about studios. They didn't want that kind of thing in their country. Talk about beauty, talk about rhythms, talk about esthetic — they knew what all the fine talk covered. One day a big countrified student came over to Stephen and asked:

— Tell us, aren't you an artist?

Stephen gazed at the idea-proof young man, without answering.

— Because if you are why don't you wear your hair long?

A few bystanders laughed at this and Stephen wondered for which of the learned professions the young man's father designed him.

conventionally just law, medicine, or theology

16 16a 16b 16c 16d 16e 16f 16g

Labels:

ch16

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment