14 14a 14b 14c 14d 14e

Dinner was served at half past six in a long plainly-furnished room. The table spread under a tall lamp of elegant silver-work wore an air of chaste elegance. It was a slight trial on Stephen's hunger to accept these cold manners and in the warmth of his relish for food he condemned this strange attitude of human beings as ungrateful and unnatural. The conversation was also a little mincing and Stephen heard the words 'charming' and 'nice' and 'pretty' too often to find them agreeable. He discovered the weak point in Mr Fulham's armour very soon; Mr Fulham, like most of his countrymen, was a persuaded politician. Most of Mr Fulham's neighbours were primitive types and he, in spite of the narrowness of his ideas, was regarded by them as a man of ripe culture. In a discussion which took place over a game of bézique Stephen heard his godfather explain to a more rustic proprietor the nature of the work done by the missionary fathers in civilising the Chinese people. He sustained the propositions that the Church is also the chief repository of secular culture and that the tradition of learning must derive from the monks. He saw in the pride of the Church the only refuge of men against a threatening democracy and said that Aquinas had anticipated all the discoveries of the modern world. His neighbour was puzzled to discover the whereabouts of the souls of the Chinese people in the other life but Mr Fulham left the problem at the door of God's mercy. At this stage of the discussion Miss Howard, hitherto silent, said that there were three kinds of baptism and her statement was accepted as a closure.

3 kinds of baptism: by water, blood or desire [info]

Stephen was a long time in doubt as to the motive of his godfather's patronage. The second day after his arrival as they were driving back from a tennis-tournament Mr Fulham said to him.

— Isn't Mr Tate your English professor, Stephen?

chapter nine included an "Epiphany of Mr. Tate" but he's otherwise unmentioned in SH. PoA2 includes Tate accusing SD of heresy

— Yes, sir.

— His people are in Westmeath. We often see him during holiday time. He seems to take a great interest in you.

— O, you know him then?

— Yes. He is laid up at present with a bad knee or I'd write to him to come over here. Perhaps we may drive over to see him one of these days.... He is a very well-read man, Stephen.

— Yes, said Stephen.

Tennis-tournaments, military bands, rustic cricket-matches, little flower shows were resorted to for Stephen's entertainment. At these functions he remarked that his godfather was very openly humoured and Miss Howard very respectfully courted and he began to suspect that there was money somewhere in the background. These entertainments did not amuse the youth; his manner was so quiet that often he passed unnoticed and remained unintroduced. Sometimes an officer would send a glance of impolite enquiry at the cheap-looking white shoes he wore but Stephen always looked his enemy in the face. After a short trial of eyes the youth could usually procure a truce. He was surprised to find that Miss Howard discharged her social duties with such apparent goodwill. He was displeased and disappointed to hear her make a pun one day — a pun which though it was not very clever raised a polite laugh from two scrupulous lieutenants. Mr Fulham was old and honoured enough to allow himself the luxury of admonishing publicly whenever occasion arose. One day an officer told a humorous story which was intended to poke fun at countrified ideas.

The story was this. The officer and a friend found themselves one evening surprised by a heavy shower far out on the Killucan road and forced to take refuge in a peasant's cabin. An old man was seated at the side of the fire smoking a dirty cutty-pipe which he held upside down in the corner of his mouth. The old peasant invited his visitors to come near the fire as the evening was chilly and said he could not stand up to welcome them decently as he had the rheumatics. The officer's friend who was a learned young lady observed a figure scrawled in chalk over the fireplace and asked what it was. The peasant said:

Killucan [map]

— Me grandson Johnny done that the time the circus was in the town. He seen the pictures on the walls and began pesterin' his mother for fourpence to see th' elephants. But sure when he got in an' all divil elephant was in it. But it was him drew that there.

The young lady laughed and the old man blinked his red eyes at the fire and went on smoking evenly and talking to himself:

— I've heerd tell them elephants is most natural things, that they has the notions of a Christian... I wanse seen meself a picture of niggers riding on wan of 'em— aye and beating blazes out of 'im with a stick. Begorra ye'd have more trouble with the childre is in it now that with one of thim big fellows.

|

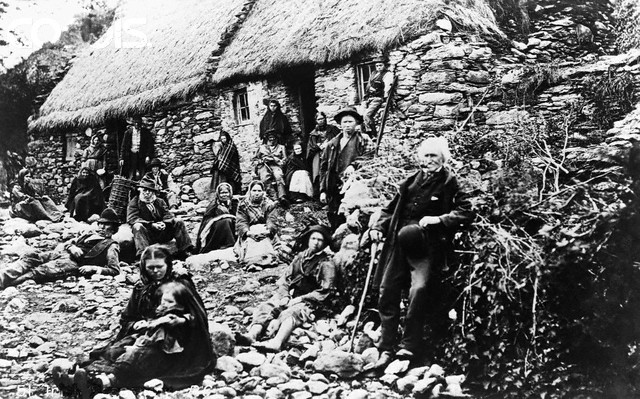

| peasants |

The young lady who was much amused began to tell the peasant about the animals of prehistoric times. The old man heard her out in silence and then said slowly:

— Aw, there must be terrible quare craythurs at the latther ind of the world.

Stephen thought that the officer told this story very well and he joined in the laugh that followed it. But Mr Fulham was not of his opinion and spoke out against the moral of the story rather sententiously.

— It is easy to laugh at the peasant. He is ignorant of many things which the world thinks important. But we mustn't forget at the same time, Captain Starkie, that the peasant stands perhaps nearer to the true ideal of a Christian life than many of us who condemn him.

— I do not condemn him, answered Captain Starkie, but I am amused.

— Our Irish peasantry, continued Mr Fulham with conviction, is the backbone of the nation.

14 14a 14b 14c 14d 14e

No comments:

Post a Comment